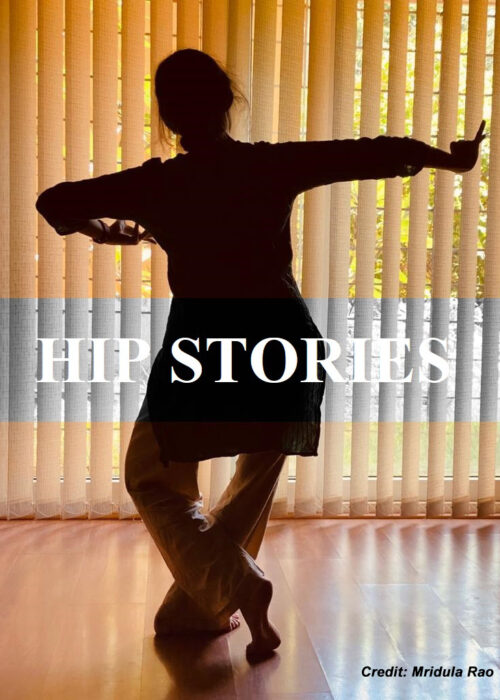

I started learning Bharatanatyam when I was 11 years old. When I explored the form’s movement possibilities in awe, I would feel an electricity pass through the various parts of my body – except in my hips.

I saw my hips only as a foundation that divided my upper and lower body and enabled my knees to turn out to create the diamond shape that we call aramandi in Bharatanatyam. The hips had to be squared, boxed, and held as they divided my body into two halves (rather than connecting the two halves). My hips did not have autonomy of their own; in fact, they acted as insulators – not allowing the movement of the legs to echo to the top and vice versa. They could not sway!

I have always had a bad turn out in aramandi. When I started exploring the field (attending lecture demos and workshops by various gurus) I realized that a great turn-out of aramandi, meant that you were a good Bharatanatyam dancer. Hips to me then became a site of intense focus and ambition so much so that I would prefer to have even conversations and discussions with friends whilst doing aramandi.

At around the same time, I started training in Kathak. The vertical stance drew me to the form and the casual hips were a welcome change from my Bharatanatyam training. In Kathak, the weight is not held in the center. It keeps shifting quickly between the legs. The ambition to square them is replaced by a gentle letting go in the hips. As I started to attend Kathak lecture demos, I encountered the word naachenewaali for the first time in my life.

“We keep our hips absolutely still when we do na-dhin-dhin-na, else you know what it will start looking like? You are not a naachnewaali.” A famous Kathak guru in Bangalore told me once. This guru loved thumris and had learned and passed on many of Bindaddin Maharaj’s compositions to her students. Thumak -ri! The word thumri comes from thumakana, I was told. But where is the thumak happening in the body, is it not the hips? I wondered.

In another workshop, I got reprimanded by a senior Guru from Pune “Itna lachak lachak ke kyon chal rahi ho?” It was the sheer disgust and anger in the voice of a very gentlewoman that completely threw me off. But the poetry exactly said this- Lachak lachak chale kadam ki chaiya (The women folk swayed as they walked towards the shade of the kadam tree). Subsequently, I too learned to fall in line, I mastered taming my hips.

When there was a resurgence of the Natyashastra discourse in the mid-2000s, I started to train in karanas as reconstructed by Dr. Padma Subramaniam. These reconstructed movements brought a fresh lease of life to my dance. It allowed for swaying, twisting, lifting, and dropping of hips. Hips were finally a conduit of echo, energy, and movement between the upper and lower halves of my body. I felt sexy as hips became available to my dance. But it wasn’t so simple to feel sexy in classical dance.