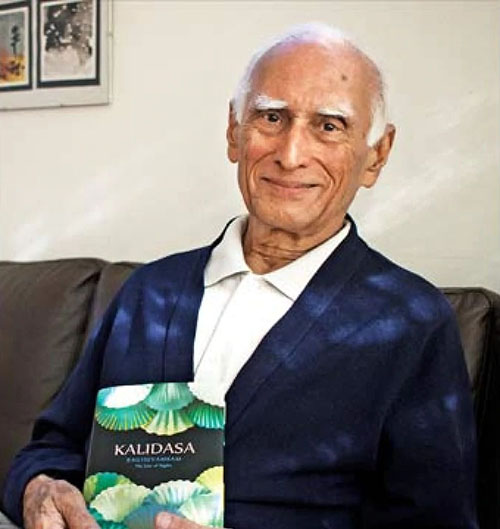

Aditya Narayan Dhairyasheel Haksar is a noted English-language translator of Sanskrit poetry, plays, and fiction. His work focuses on satiric, secular, and erotic literature, often overlooked by Orientalist scholars in favour of religious and administrative texts.

Speaking to the press in 2012, Sh. A.N.D. Haksar noted that colonialists had formed the impression that Sanskrit literature was “very ancient, very important, very good quality, and its main focus is religion and philosophy.” Less attention was paid to Katha literature, written in simpler language than the refined Sanskrit used at court. Katha tales often featured parables, or romantic and sexual themes, and included comic and colloquial works.

In 20 volumes of translation published over 18 years, Sh. Haksar has focused on these secular and, often, previously untranslated works of Sanskrit literature. These include the Madhavanala Katha, published as Madhava and Kama, and the SamayaMatrika, “The Courtesan’s Keeper”. His translations also highlight the confluence between Sanskrit and Persian poetry: take for instance A Tale of Wonder – Kathakautukam, a 15th-century poem by the Kashmiri poet-scholar Srivara that is a Sanskrit version of a Persian poem.

Sh. Haksar will address Studio Abhyas on 5th November 2020 (Thursday) at 7 pm IST, on the popular perception of Sanskrit as a language of theology, doctrine, and scripture, and on the factors that led him to his own choice of secular, comic, satiric and erotic texts.

Some excerpts of his writing are reproduced below –

Three Hundred Verses: Bhartrihari: Musings on Life, Love, and Renunciation (Penguin, 2017)

| 1.

I bow to that radiance, peaceful and still, endless, unbounded by space and time, which is the spirit and only known through self-awareness.

|

Love in Spring and Summer

45. At this time does a koel look longingly at mango trees with budding blooms that store the fire of loneliness in a traveller’s wife its agony further enflamed by breezes from the southern hills scented with new trumpet flowers

|

| 6.

I have always longed for her, but she does reject me, indeed she wants another man who chases someone else a maid who is to me attracted: a curse on her and on that man, on the other girl, on Love, on me.

|

100.

There can be, the poet says, one god: Keshava or Shiva; one friend: a king or an ascetic; one abode: a town or a forest; and one bride: a beauty or a cave. |

| On Wealth

31. One who has money is considered well born, learned, discerning, well versed in scriptures, an eloquent speaker, and good-looking too: all merits depend on gold.

|

“Life and Love: An Allegory”, excerpted from The Seduction of Shiva: Tales of Life and Love(Penguin, 2014)

There lived in times of yore a famous prince by the name of Puranjan. He had searched the whole earth for a worthy habitation but had found none. This had saddened him, for he longed for all kinds of enjoyment, but of all the cities he had seen, not one had been found adequate for his pleasures.

One day, in the land south of the Himalayas, he saw a city with nine gates. It possessed all the good attributes—battlements and moats, gardens and terraces, latticed windows, and royal gates. It was full of great mansions crowned with domes of gold, silver, and steel. The palaces in that city were adorned with emeralds and rubies, crystals and pearls, opals and sapphires, and shone like the citadels of the serpent kings. They were surrounded by avenues and squares, markets and halls of assembly, places for sport, and for relaxation, with benches of coral and many flags and banners.

Outside that city was a beautiful park full of wonderful trees and creepers, with birds singing and bees humming over the flowers. There was a lake within the park, and the verdure around it rustled in the mild spring breezes and the cool spray of waterfalls. The animals in that park were peaceful and harmless; and the nightingale’s call beckoned the traveller to rest in it.

Wandering in that marvelous woodland, Prince Puranjan beheld a damsel coming his way. With her was a retinue of ten attendants, each the leader of a hundred maidens, and a five-headed serpent guarded her. She was in the first bloom of youth. Her complexion was dusky, her nose and temples, teeth and mouth, and the curve of her waist were of exceeding beauty. She wore a yellow garment and a girdle of gold. Rings sparkled in her ears and the anklets on her feet tinkled as she walked, modestly covering a rounded bosom which testified to her flowering charms. In truth, she looked like a goddess. And she was in search of a worthy husband.